Macro

Lenses: Magnification, Depth of Field

and

Effective F-Stop

A proper macro lens is designed to eliminate aberrations, focus colors and attain maximum sharpness on close-up subjects

Macro is one of the more challenging types of photography from a technical perspective, and choosing the right lens for macro work can be similarly perplexing. The word macro is often (and incorrectly) used interchangeably with “close-up.” The two are not synonymous. While a macro image may indeed be made at a close distance to the subject, it’s the magnification of the subject, and not its proximity to the lens, that defines macro photography.

Macro is the photo opportunity that’s always available. You can find good close-up subjects just about anywhere. All you need is a way to make your camera focus close enough. Dedicated macro lenses are the best option because they can focus from infinity down to close enough to produce a life-size (1:1) magnification at the image plane. Macro lenses also are optically optimized for close focusing distances, so they produce better results at such close range than non-macro lenses used with extension tubes (and lenses with extension tubes attached can no longer focus out to infinity).

Most macro lenses also are well corrected for flat fieldwork, such as photographing stamps and coins, which may or may not be useful for nature photography. The main drawbacks of macro lenses are that they’re generally bulkier and more costly than non-macro lenses of equal focal length, although the differences today aren’t nearly as great as they were some years ago.

Macro Lens Magnification

What makes a “true” macro lens? Many lenses are labeled “macro” by manufacturers because they are able to focus at very close distances, but that doesn’t make them true macro lenses.

When we talk about magnification regarding macro lenses, we’re talking about magnification at the image plane. You can blow up the image well beyond that on your computer monitor or in a print, and that can make the macro subject much bigger than in real life—even if you shot it with a non-macro lens. But the macro lens gives you the advantage of more pixels recording the subject instead of being thrown away. The image of the subject will be recorded bigger in the frame, with the potential to reveal more detail.

A true macro lens will have 1:1, or 1x magnification (or greater). What this means is that the size of the subject projected on the image plane by the lens is its actual physical size—a flower that’s 2 centimeters in diameter will be rendered 2 centimeters in diameter on the sensor.

It’s important to note that sensor size does not affect the magnification power of the lens itself. This is a common misconception. The “crop factor” of smaller sensors is just that: a crop. This makes an object appear magnified in relationship to the sensor’s frame because the image circle produced by the lens is larger than the sensor. So for practical purposes, you do get more magnification with the smaller sensor in that the subject fills up more of the image frame. The actual magnification produced by the lens at the image plane doesn’t change; rather, it’s the amount of that image that each sensor size sees that changes.

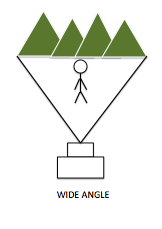

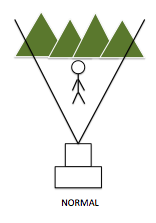

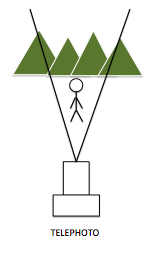

Macro Lens Focal Lengths

Focal length is an important consideration in macro photography because it determines your “working distance” from the subject. The longer the focal length, the greater the working distance to achieve 1:1 magnification. With a 100mm macro, you’ll be twice the distance from your subject than with a 50mm macro. This is beneficial when photographing live subjects that may be alarmed by your proximity. You’re also less likely to block ambient light on your subject—another inherent challenge of macro photography—when working from a greater distance.

A normal (50mm for a full-frame camera) macro lens produces its 1x magnification at a distance of around seven to eight inches, a short tele macro lens (100mm for a full-frame camera) at around 12 inches and a tele (200mm for a full-frame camera) at around 19 inches. Shooting closer to the subject expands perspective, while shooting from farther away compresses it.

Minimum Focusing Distance Of Macro Lenses

Unlike magnification, the minimum focusing distance of a lens is a relatively straightforward concept. This is the closest distance your lens can be positioned from the subject and still achieve sharp focus. You’ll observe that the minimum focusing distance increases along with focal length. That’s because for 1:1 magnification, as noted in our discussion of focal length, you’ll need to be closer to the subject with a wider lens than you will with a telephoto lens.

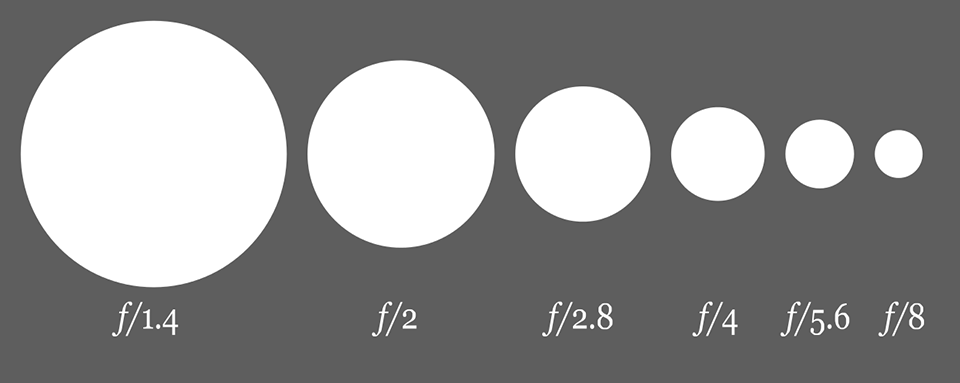

Macro Lens Depth Of Field

Most normal and short tele macro lenses have a maximum aperture of ƒ/2.8, while most tele macros have a maximum aperture of ƒ/3.5 or ƒ/4. Due to the limited depth of field at macro shooting distances, these apertures let you produce dramatic selective-focus effects; focus on a particular part of a flower or the eye of an insect, and everything closer to the camera or farther away blurs nicely.

If you want an entire insect or flower to be sharp, you’ll have to stop the lens way down to increase depth of field. Even then you probably won’t get the entire subject sharp due to the very limited depth of field at very close shooting distances. Stopping the lens way down introduces the effects of diffraction—at very small apertures, light bends around the edges of the aperture, reducing overall sharpness, even as increased depth of field increases it.

Most professional macro photographers use electronic flash to illuminate their subjects. Electronic flash offers two major benefits; it’s bright at macro range, allowing you to stop all the way down to increase depth of field, and its very brief duration at short range (1⁄10,000 sec. and shorter) minimizes the effects of camera shake and subject movement. Special macro flash units mount on the lens and allow you to set them to provide even lighting or directional lighting.

Focusing Macro Subjects

Most macro lenses in production today offer autofocusing, but it’s generally best to focus a macro subject manually. That’s the only way to be sure focus is exactly where you want it. If a particular magnification is desired, set that (most macro lenses have magnification or reproduction ratio reference markings on the barrel), then slowly move the camera in on the subject until it comes into focus in the viewfinder or on the LCD monitor if you’re using Live View mode. Once you’ve achieved focus this way, you can activate the AF system to maintain focus if the subject is moving. If you just want the biggest image of the subject, set the lens to its minimum focusing distance, and move in until the subject appears sharp in the finder. Of course, you’re free to position the camera, then adjust focus using the focusing ring or even AF, which can work, too.

Macro Lenses & Image Stabilization

A tripod can hold the camera steadier than we can, and can lock in a composition of a nonmoving subject so you don’t accidentally change it as you squeeze off the shot. For the sharpest, most controlled macro compositions, a tripod is especially essential for macro work. At this level of magnification, even the smallest movements can degrade sharpness.

Working from a tripod also lets you experiment with depth-of-field by varying your aperture without changing your composition, and can be further used for focus stacking techniques. But it can sometimes be difficult to position the camera exactly where you want it for a macro shot using a tripod, so many macro shooters work handheld, using electronic flash’s brief duration to minimize blur due to camera shake. You may want to try it both ways to see which works best for your macro photography. A monopod is a good compromise, making it much easier to position the camera right where you want it, yet providing more support than pure handholding. Still, having the option of optical image stabilization is a nice alternative when using a tripod isn’t practical or possible.